This is a post from team member Josh Cowls, cross-posted from his blog. Josh is also on Twitter: @JoshCowls.

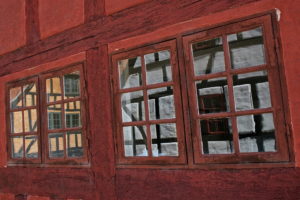

I am in Aarhus this week for the ‘Web Archiving and Archived Web’ seminar organised by Netlab at Aarhus University. Before the seminar got underway, I had time to walk around ‘The Old Town’ (Den Gamle By), a vibrant, open-air reconstruction of historic Danish buildings from the eighteenth century to the present. The Old Town is described as an open-air museum, but in many ways it’s much more than that: it’s filled with actors who walk around impersonating townsfolk from across history, interacting with guests to bring the old town more vividly to life.

As it turned out, an afternoon spent in The Old Town has provided a great theoretical context for the web archiving seminar. Interest in web archiving has grown significantly in recent years, as the breadth of participants – scholars, curators and technologists – represented at the seminar shows. But web archiving remains replete with methodological and theoretical questions which are only starting to be answered.

One of the major themes already emerging from the discussions relates exactly how the act of web archiving is conceptualised. A popular myth is that web archives, particularly those accessible in the Internet Archive through the Wayback Machine interface, serve as direct, faithful representations of the web as it used to be. It’s easy to see why this view can seem seductive: the Wayback Machine offers an often seamless experience which functions much like the live web itself: enter URL, select date, surf the web of the past. Yet, as everyone at the seminar already knows painfully well, there are myriad reasons why this is a false assumption. Even within a single archive, plenty of discrepancies emerge, in terms of when each page was archived, exactly what was archived, and so on. Combining data from multiple archives is exponentially more problematic still.

Moreover, the emergence of ‘Web 2.0′ platforms such as social networks which have transformed the live web experience have proved difficult to archive. Web archiving emerged to suit the ‘Web 1.0′ era, a primarily ‘old media’ environment of text, still images and other content joined together, crucially, by hyperlinks. But with more people sharing more of their lives online with more sophisticated expressive technology, the data flowing over the Internet is of a qualitatively richer variety. Some of the more dramatic outcomes of this shift have already emerged – such as Edward Snowden’s explosive NSA revelations, or the incredible value of personal data to corporations – but the broader-based implications of this data for our understanding of society are still emerging.

Web archives may be one of the ways in which for scholars of the present and future learn more about contemporary society. Yet the potential this offers must be accompanied by a keener understanding of what archives do and don’t represent. Most fundamentally, the myth that web archives faithfully represent what the web as it was needs to be exposed and explained. Web archives can be a more or less accurate representation of the web of the past, but they can never be a perfect copy. The ‘Old Town’ in Aarhus is a great recreation of the past, but I was obviously never under the illusion that I was actually seeing the past – those costumed townsfolk were actors after all. I was always instinctively aware, moreover, that the museum’s curators affected what I saw. Yet given that they are, and given the seemingly neutral nature implied by the term ‘archive’, this trap is more easily fallen into in the case of web archives. Understanding that web archives, however seamless, will never be a perfectly faithful recreation of the experience of users at the time – or put even more simply, that these efforts are always a recreation and not the original experience itself – is an important first step in a more appropriate appreciation of the opportunities that they offer.

Moreover, occasions like this seminar give scholars at the forefront of preserving and using archived material from the web a chance to reflect on the significance of the design decisions taken now around data capture and analysis for generations of researchers in future. History may be written by the victors, but web history is facilitated, in essence, by predictors: those charged with anticipating exactly which data, tools and techniques will be most valuable to posterity.