This post is by project team member Josh Cowls of the OII.

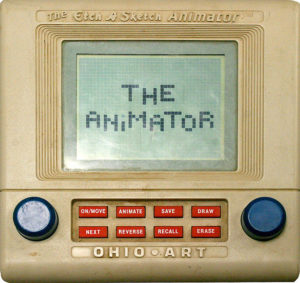

In March 2012, as Mitt Romney was seeking to win over conservative voters in his bid to become the Republican Party’s presidential nominee, his adviser Eric Fehrnstrom discussed concerns over his appeal to moderate voters later in the campaign, telling a CNN interviewer, “For the fall campaign … everything changes. It’s almost like an Etch A Sketch. You can kind of shake it up, and we start all over again.” Fehrnstrom’s unfortunate response provided a memorable metaphor for the existing perception of Romney as a ‘flip-flopper’. Fehrnstrom’s opposite number in the Obama campaign, David Axelrod, would later jibe that “it’s hard to Etch-A-Sketch the truth away”, and indeed, tying Romney to his less appetising positions and comments formed a core component of the President’s successful re-election strategy.

Clearly, in the harsh spotlight of an American presidential election, when a candidate’s every utterance is recorded, it is indeed “hard to Etch-A-Sketch the truth away”. Yet even in our digital era, a time at which – as recent revelations have suggested – vast hordes of our communication records may be captured every day, the Romney example is more the exception than the rule. In fact, even at the highest levels and in the most important contexts, it can be surprisingly easy for digitised information to simply go missing or at least become inaccessible: the web is more of an Etch-A-Sketch than it might appear.

Take the case of the Conservative Party’s attempts to block access to political material pre-dating the 2010 general election. It remains unclear whether these efforts were thoroughly Machiavellian or rather less malign (and in any case a secondary archive continued to provide access to the materials). Regardless, the incident certainly challenged the prevailing assumption that all materials which were once online will stay there.

In fact, the whole notion of staying there on the web is an illogical one. Certainly, the web has democratised the distribution of information: publishing used to be the preserve of anyone rich enough to own a printing press, but with the advent of the web, all it takes to publish virtual content is a decent blogging platform. Yet it’s crucial to remember that the exponential growth in the number of publishers online does not mean that the underlying process of publishing has entirely changed.

Although many prominent social media sites mask this well, there is still a core distinction on any web page between writer and reader. In fact, this distinction is baked into the DNA of the web: any user can freely browse the web through the system of URLs, but each individual site is operated, and its HTML code modified, by a specific authorised user. (Of course, there are certain sites like wikis which do allow any user to make substantial edits to a page.) As such, the distinction between writer and reader remains relevant on the web today.

In fact, there is at least one way in which the web entrenches more rather than less control in the hands of publishers as compared with traditional media. Spared of the need to make a physical copy of their work, publishers can make changes to published content without a leaving a shred of evidence: I might have removed a typo from the previous paragraph a minute before you loaded this page, and you’d never know the difference. And it’s not only trivial changes to a single web page, but also the wholesale removal of entire web sites and other electronic resources which can pass unnoticed online. At a time when more and more aspects of life take place on the Internet, the importance of this to both academics and the public more broadly is becoming increasingly clear.

This of course is where the practice of web archiving comes in. I’m of the belief that web archiving should be conceived as broadly as possible, namely as any attempt to preserve any part of the web at any particular time. Contained within the scope of this definition is a huge range of different archiving activities, from a screenshot of a single web page to a sweep of an entire national web domain or the web in its entirety. Given the huge technical constraints involved, difficult decisions usually have to be made in choosing exactly what to archive; the core tension is often between breadth of coverage and depth in terms of snapshot frequency and the handling of technically complicated objects, for example. These decisions will affect exactly how the archived web will look in the future.

Yet our discussion of the challenges around web archiving shouldn’t take place in a vacuum. Certainly the archiving of printed records comes with its own challenges, too, not least over access: in the case of Soviet Russia, for example, it was only after the Cold War had finished that archives were open to historians, and then only partially. Web archives in contrast have the virtue that they can be – and typically are – made freely available over the web itself for analysis. And, just as with the spurt of scholarship that followed the opening of the Soviet archives, we should be sure to see the preservation of web archives not merely as a challenge but also as an opportunity. Analysing web archives can enhance our ability to talk about the first twenty five years of life on the web – and unearth new insights about society more generally.

A central purpose of this project is to support the work of scholars at the cutting edge of exactly this sort of research. There’s just a couple more days to submit a proposal for one of the project’s research bursaries; see here for more details.